Illuminations

Lindsey Drager

Light falls and in falling gives shape to what lies below: the outline of a town from above.

Then, closer: snaking lines become rivers and roads, the ordered patterns of multicolored squares become neighborhoods. Closer still and there are rooftops and patches of green that become parks, playgrounds, yards. Now there are cars and mailboxes, bicycles abandoned in driveways. Light falls on all these things and keeps falling and then, inside a house surrounded by trees, there she is: the woman, age thirty-four, sitting at her mother’s kitchen table.

On the table: photographs from her youth. The woman is looking out her mother’s window at the way the light falls on the afternoon. It is raining and everything she sees is cast through the sky’s water meeting Earth. Inside her now, there: there is something inside her that is trying to see through the rain to the other side of the road, but she cannot. It seems to her that some things can’t be seen.

She has just recalled an event, going through these photographs. She had recently released them from their locked lives inside albums where they had sat dormant for twenty-five years, but because yesterday was her mother’s funeral, she had scanned the photos to run on a loop on screens at the funeral home.

Before she’d been overwhelmed by this recollection, this revelation, she had been sliding the print pictures around the table into a kind of order, had watched her mother move through the years. Her grief pulls her mind in strange directions. A photograph, just paper and manipulated light. She has been thinking about light, was thinking about light just now when the memory came to her, as she glanced outside.

The photo that has prompted her unease contains an image of the woman as a child, wearing her fossil pajamas. She is in her mother’s lap and her mother is kissing the side of the child’s neck and tickling the child’s belly and the child is fixed in the image mid-laugh, body tilted sideways to avoid her mother’s hands. The child is laughing. The woman now is grieving. But also, a spark of recognition – some memory lingering on an edge, rekindled. It is piercing her mind, but then those dots of perception swell and widen, become gaps, and now, here it is – the opening that permits the memory to return.

It is her mother, telling her daughter that not long ago, the mother had been taken. The mother had been seized, acquired, abducted, but not by a human being. It is her mother, kneeling down to the level of the child in her fossil pajamas, her mother telling her that she’d been taken by something not from here, taken to a world beyond the Earth. The child had looked down at her pajamas, thought of the way that fossils were from a time before people. Thought then of space and the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs off. How the asteroid made way for the reign of humans. The photo is dated to make the girl six.

Her body is exhausted from the bureaucracy of burying a parent. Managing the trust, paying the hospital expenses, executing the will. Her thinking is looping and orbiting, failing to end, just like the digital timeline of pictures at the funeral home. One image after another. One moment, then the next. Her body is exhausted from the work of burying a parent and, too, she is still grieving. These past few days, even as her mother is gone, she falls asleep to the sound of her voice and the smell of her skin. But now – this memory. The old-new knowledge is surfacing and all her sorrow and all her frustration, all her anguish at what has been the end of her mother is fading in the face of this fact.

It is raining and the light seems wrong – unnatural the woman thinks – and then the memory makes chaos of her body. She is sweating and she suddenly registers the pulsing of her blood in the veins in her temples. The woman thinks back to her fossil pajamas, remembers that she had written her name on the inside of the shirt as well as the bottoms.

She is at the sink and she is thinking: her mother believed she was taken. Or did in that moment. Did then. What strange paths the mind chooses to take as it anchors itself to belief. It was never mentioned again. She wracks her brain – no, never. It was never thereafter discussed. Perhaps her mother had said it off the cuff, a sort of dismissive gesture. A way to get attention. Or maybe as a way to warn the girl. A cautionary tale or a lesson that being born means you have been given a body, and a body is brittle, is fragile, is susceptible to abrasions of the skin and heart. A body can be seized.

And yet, this memory. She recalls her mother telling her and weeping. Tears were streaming down her face. If this were just a warning, she thinks, that would not have happened. As she is coming to wrap herself around it, the memory starts to crystallize as fact.

This distills the woman.

She breathes, sweats. Wraps her hands around her neck. Watches the rain fall so hard she can’t see the road.

She loves her mother – even in death her mother is present and the woman will use present tense, she will, the woman is using present tense – she loves her mother with a kind of raw devotion that perhaps only comes from a daughter who has seen her mother endure the things her mother endured. Because the real tragedy is that there were good years after all the bad. There were good years – three or four in succession – running right up until her heart attack last week. She was medicated, went to her therapies, worked her tools to get to a much better place. For the last three years she knows that her mother was rational. Her mother knew what was real and what wasn’t, after years of that line being blurry and slippery in her mind.

She was rational, but what does that actually mean? To reason, to abide by reason. To be lucid. To be able to see.

So, the woman thinks, downing another glass of water, one hip jutting out as she uses both arms to hold herself over the sink. So, the woman thinks, it could be that she believed it. That something seized her mother, literally or figuratively. And the truth is, the woman thinks, as she lifts her eyes from the bottom of the sink to the strange light coming through the rain outside, the truth is that it might be easier. For the woman.

It might be easier to believe that a very concrete something, a very specific and defined something changed her mother one night when her mother was taken by something not human, taken from the Earth. If something had changed in her mother that early – the woman’s heart hurts thinking of it – then that would be an origin. A source. Something to point to and say it began here, then. Everything her mother endured and struggled with, managed and lost – all of it would become a product of that experience. If the woman chose to believe this thing about her mother – that she’d been taken as a young woman, taken beyond Earth – that could be a cause for every effect the woman had witnessed in the narrative of her mother’s life.

She recalls her mother once claiming that whales, long ago, had legs. She was a child then and had not believed it. The girl knew evolution moved in only one direction. We all came from the water, but what creature would go back? Years later, she’d read in Scientific American that this theory was real. She remembers the following article was about a strangely shaped comet that astronomers proposed might be an ancient vessel from life beyond Earth.

Your eyes, her mother had said, can tell you lies. Stay skeptical.

The woman picks up the photo, looks into her past. When the fossil pajamas started to fall apart, holes in the knees and elbows, tears at the hems, her mother insisted she throw them away. The woman recalls she had cried when she watched her mother take them from her dresser one evening and place them in the garbage bin.

Her mother had made her watch.

Somehow that made it hurt more.

The woman is breathing and sweating; the light outside feels wrong and wild. But she is staying skeptical. She is staying skeptical because, she thinks, there is something to loving another that is rooted in unknowability. There is something about human love that is tied to not-knowing and finding a way through the unknowability toward something close to trust.

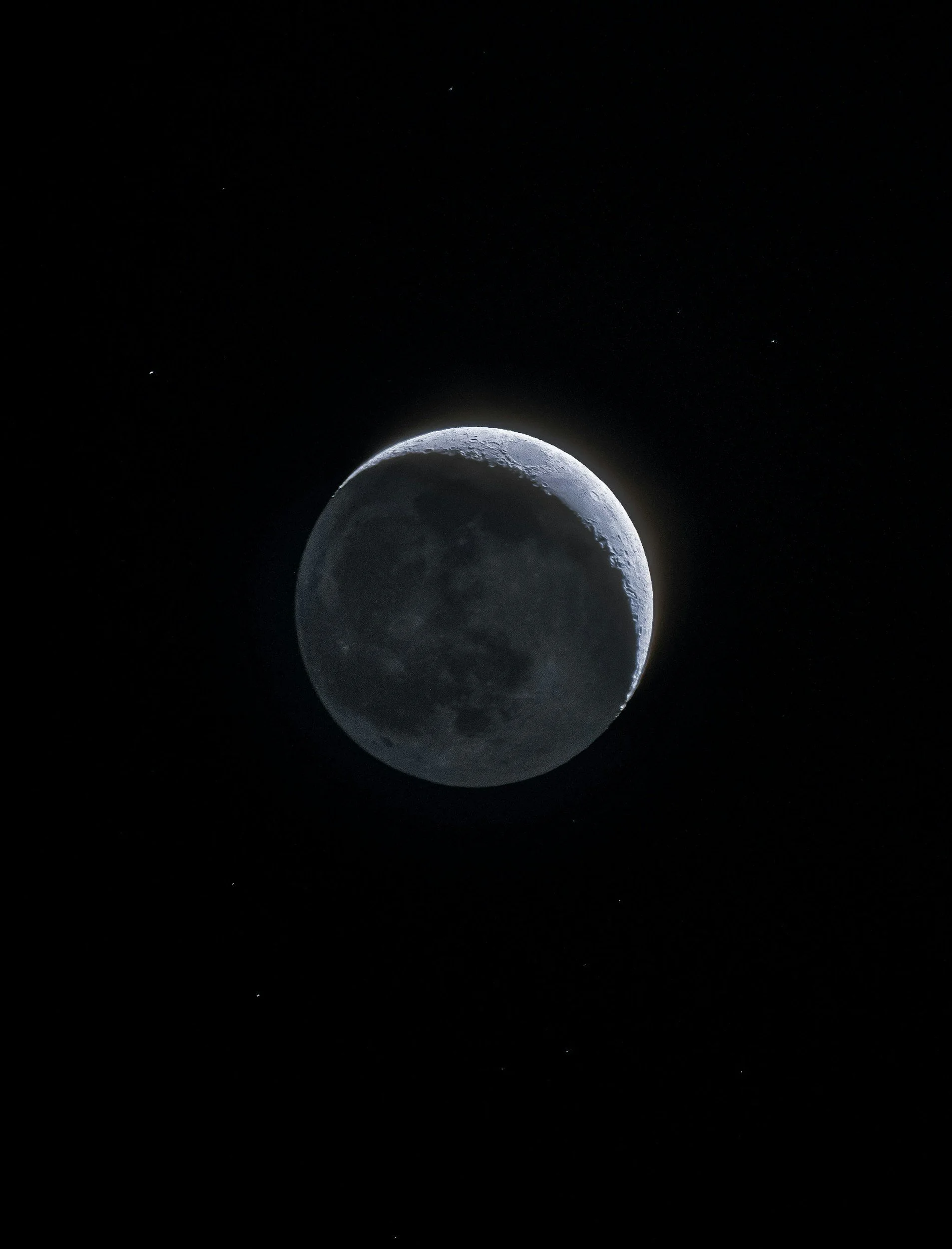

Light fills the sky in the form of stars. The pinpoints of light make the sky above the house sentient, and now there is movement outside the woman’s cognition. Movement from inside to outside her head, then outside the house, toward the light in the sky. Up and away and further, so that the roof of the house and the lights on the street become less like material objects and more like abstract shapes and then it is all just valleys and corridors of light across a darkened landscape. She is there still, looking for the things she needs to understand the woman in whose body she grew for nine months thirty-four years ago. It is silly, in the end, to desire so much to hold onto things when everything that can be known is ephemeral and fleeting.

The light is now just swaths of brightness on a sphere that is turning, though it’s difficult to feel. Difficult to know, too, that it is orbiting the sun.

From the surface of the moon now, from here, the light on Earth is beautiful. It is radiant.

But there is something unnatural here, too, something uncanny, when for so long – for millions of years – when darkness fell on the orb that is Earth, there was nothing to contest it. That orb is luminous now, here, beyond the moon and further, as Earth becomes just a pinprick in the sky. Then light becomes time, first light minutes then years, but the planet sits there on the same plane as the other planets in one solar system in an arm of a galaxy that is one in an infinite spectrum of places that are called the opposite of time. A spectrum of places called space.

It is beautiful, that planet and its human light. Were you to see it from above, you would think that sphere looked like something living, something pulsing and churning. You’d think that whole world was one single being, breathing in tandem with the rest of the patterns that govern the globes of the cosmos.

But your eyes can tell you lies and here is a bit of proof: In the basement of the mother’s house, near the bottom of the tallest shelf, lies a box which contains keepsakes, a time capsule of a daughter’s life. The woman will find the box tomorrow. Right now she doesn’t know that it exists. Inside the box are things the woman believes were thrown away decades ago: awards and accolades, trophies and prizes. Paintings and stories and sculptures.

And, too, inside that box lies the daughter’s fossil pajamas.

Fiction

16 January 2026

Lindsey Drager is the author of the novels The Sorrow Proper (Dzanc, 2015), The Lost Daughter Collective (Dzanc, 2017), The Archive of Alternate Endings (Dzanc, 2019), and The Avian Hourglass (Dzanc, 2024). These books have been listed as a “Best Book of the Year” in The Guardian and NPR; twice been named finalists for Lambda Literary Awards; and have been translated into Spanish and Italian. Recent short fiction can be found in The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, Iowa Review, Colorado Review, Conjunctions, and elsewhere. She is a recipient of a 2017 Shirley Jackson Award, a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Prose, the 2022 Bard Fiction Prize, a 2025 Pushcart Prize, and a 2025 O. Henry Prize. Drager is also currently the fiction editor of West Branch and an assistant professor at the University of Utah where she volunteers in the University Prison Education Project (UPEP)