Words Rising: Sculpting Poetry Off the Page

Review by Camille LeFevre

Review

19 February 2025

CAConrad: 500 Places at Once

CAConrad & Fivehundred places

Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson, September 13, 2024 – February 16, 2025

Mary Ruefle: Erasures

Mary Ruefle

University of Arizona Poetry Center, September 17, 2024 to February 8, 2025

Begin with the body. Your body. The body of the earth. The body of a book.

Bring the mind, the poetics of space, into the conversation.

Free all words from the confines of the page: templates, margins, the sentence, punctuation.

Feel the words rise from the page and gather with a sensitivity guided by your sensibility; they may move, shift, disassemble, or reconfigure, seemingly of their own accord.

Be startled at what is revealed: poetry given agency to soothe or stimulate, uplift and delight. To become sculptural, kinesthetic, and wholly original.

Such is the work, and the genesis of such work, in two recent poetry exhibitions in Tucson, Arizona: Mary Ruefle: Erasures, at The University of Arizona Poetry Center, and CAConrad: 500 Places at Once, at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

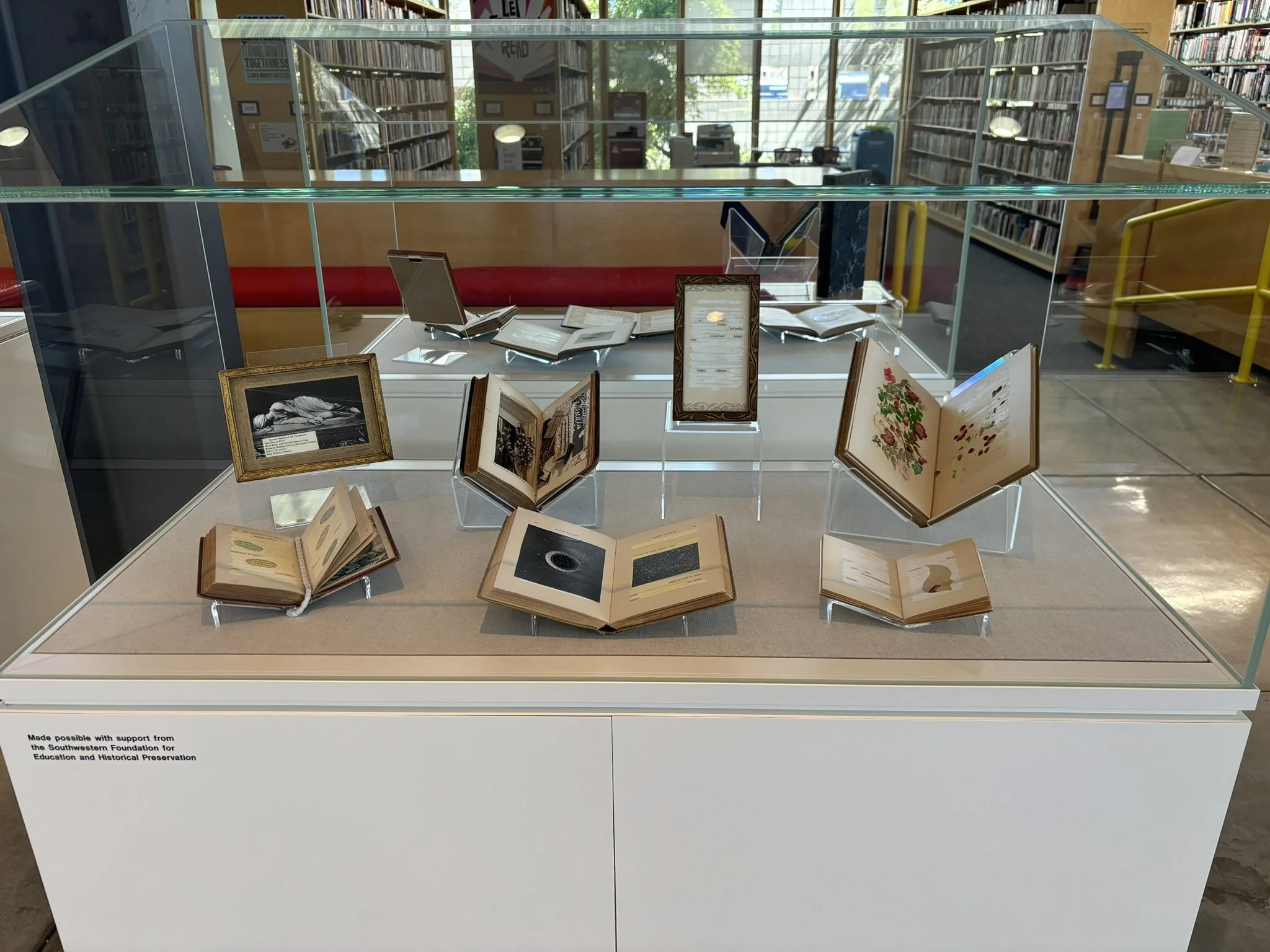

Ruefle, much-published, critically acclaimed, has been altering books since 1998, more than 100 texts, through processes of erasure and collage. A process, she says, in a talk at Bennington College, of “creating a new text by disappearing the old text that surrounds it.” I enjoyed watching this video at the Poetry Center (if you’ve read the poet’s Madness, Rack, and Honey, for example, you know how bracing, formidable, and ultimately hilarious Ruefle can be) while sitting in a comfy chair and perusing a few of Ruefle’s erasure books, my fingers lightly caressing their pages made tactile and thickened by paste, image layering, and the rippling effects of white-out.

courtesy of the University of Arizona Poetry Center

For the pieces in the exhibition, she also used markers and gouache to partially cover original texts in an act of poetic intervention – via mind and hand – that reveals new voices, phrases, and narratives. Rather than excavating a poem from the pages of an old book (she picks them up from used bookstores) she “bandages” some words while letting others “seep out” to find “new societies under the old ones” in an act of poetic archaeology. Having spent the first half of her life putting words into the world, she says she intends to spend the last half taking them out.

Neither redaction nor censorship, her process is an aesthetic, not political, one, Ruefle argues. Political erasure might seek to confront hegemonic language in old texts, and in “erasing” it, make space for new and better stories – including, for example, the Indigenous narratives that can be found and uplifted from underneath stories of the white, male, heteronormative “West.” But that is not Ruefle’s project. Without doubt, many of her erasures are ironic, comical, pleasurable plays on meaning with image and word. On one page, covered in white-out, Ruefle pastes the text “Mary turns around and says:” cut out from another book. Continuing on the overleaf are the extant words “here is the / thread / running through the narrative,” while dark green, red, and white thread tangle across the pages. In another book, the words “COMPREHEND QUICKLY” are pasted below vintage pictures of pansies and cartoon characters wearing pansy heads. Together, they face a page whited-out, as if snow-covered by a blizzard, except for “spring / is always possible to recognize / he / kept shouting.” The erasure of nearly all the text, its blackness grayed to ghostly or shadowlike beneath the white-out, emphasizes or underscores the crisp correspondence between words remaining and images added.

courtesy of the University of Arizona Poetry Center

Also on display were constructions that moved beyond the book while staying firmly ensconced in the power of text – one being a shallow wooden box, with the words “SHALL WE MEET AGAIN” on its lid, filled with dried insect carcasses and a small bird skull. Her Whitman’s Sampler box contained thin glass slides, each one with a handwritten line from a poem by Walt Whitman, indexed by title inside the candy-box cover. The painstaking quality of Ruefle’s constructions evidences a bodily practice rich with materiality and unapologetic exuberance. Paging slowly through Ruefle’s erasure books, listening to her speak of her process, and studying her poetic inventions mounted in vitrines conjured in me tremendous awe and joy.

courtesy of the University of Arizona Poetry Center

Across town, CAConrad’s exhibition of three-dimensional poem sculptures, selected from the poet’s collection Listen to the Golden Boomerang Return, instantly calmed my nervous system and invited contemplation. Conrad crafts poems through queer somatic inquiry and ritual, often in nature, typically incorporating sound, eating, and other tactile experiences. The bodies of these poems flowed uninterrupted down human-scaled white placards cut and shaped to glaciate – by that I mean smooth – the viewer’s sensibilities, while igniting memory of our responsibility to the earth. They were poetic figures, their shapes implying movement, placed within a gallery painted cerulean blue, and the effect was oceanic. I sat a while, letting myself drift between the poetic figures.

The poems themselves reference the refrigerated bodies of COVID-19 victims, gun and male violence, animal death, ecological destruction, a love relationship – portraying our entanglements with a spiritual resonance that honors even that which haunts us: “the forest / my car never / intended to be / a meat grinder / another face going / under the waves / we felt awful after / hitting the deer / we made love / and slept with / one of his / antlers / between / us.” The poems are alive; Conrad has said: “My poems are breathing wild creatures. They stand on the bottom of the page, vibrating in the center of their bodies.” In their presence, we vibrate with them, awash in meaning that circles continuously through time, their shapes creating geographies or states of being within the universe.

500 Places at Once, MOCA Tucson, 2024. Photographs by Julius Schlosburg (@catsphotoshoot), copyright © jpop photon, 2024.

I wanted to stay a while, longer than possible, attending to their embodiment – and my own, now infused with Conrad’s poetry. But I ventured beneath a scrim, with another of Conrad’s poems, into the next room, where chapbooks published by Jason Dodge’s Fivehundred places sat on a shelf. Fittingly, there was a book by Ruefle, another by Conrad – both poets back on the page, grounded, perhaps, in the poetic origins from which their imaginations, given physicality by their investigations in embodiment, have risen and found new form.

500 Places at Once, MOCA Tucson, 2024. Photographs by Julius Schlosburg (@catsphotoshoot), copyright © jpop photon, 2024.

Their poetic art objects, as evidenced in these two exhibitions, disclose the viscerality of their creative impulses: Conrad’s walking, listening, absorbing, refracting; Ruefle’s collecting, cutting, covering, combining. Like all poets, they sculpt. But in making and re-making, they free words from the page, inviting us to hold, witness, read, and process the poetic impulse in performative ways equal to their own – as embodied, even ritualistic, art.

As an arts journalist for 30+ years, Camille LeFevre wrote for publications (online and print) from Architectural Record to Audubon, Craft to The Nature Conservancy, Dance Magazine to Midwest Design, Hyperallergic to The Line, Metropolis to Southwest Contemporary. She has written books on dance and architecture. Her poetry and creative nonfiction have appeared in, or are forthcoming, in The Dodge (nominee: Best American Nature Writing, Best American Essays), Unleash Lit, Bridge Eight, Brevity Blog, Electric Lit, The Winged Moon, The Ekphrastic Review, Thin Air, and other publications. In 2023, she was awarded the Scuglik Memorial Residency in ekphrastic writing at Write On, Door County, in Wisconsin. She teaches arts writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, and ekphrastic writing workshops in galleries. She lives in Northern Arizona.